Agile Hot Dogs

Projects are usually painful endeavors. Everything takes longer than expected. Task relevance is directly proportional to the variety of its dependencies. Product Owners and Project Managers’ technical authority is typically infinitesimal, whereas engineers’ technical authority expands to infinity. The former are enthusiastic but lack leverage, the latter are beaten by life and they often couldn't care less. Projects are complicated, and the life of a project manager is nothing short than tormented. But, are projects complicated because the products they are supposed to help creating are complicated? Or is there any inherent self-inflicted complication just because it is a project and we people haven’t yet figured out how to coordinate collaborative work in a painless way?

Think about this. You are hungry, and for some reason you are craving a hot dog. What do you do next? Say there is a convenience store not far from where you are. Therefore, you go there and, well, ask for a hot dog. Then, the clerk goes and gets some bun, then picks a sausage from the grill. Next, he will surely ask if you want any condiment, say mustard —let’s assume you say yes— he puts the sausage in the bun, adds the mustard, wraps the thing up in some paper, you pay, and off you go. You’re now munching a hot dog, and your hunger will hopefully decrease soon after, as your cholesterol may slightly increase. Not very complicated, yeah?

Now let’s assume you, instead, go to another convenience store which is run by an eccentric bunch who used to be part of the engineering team in some misfortuned tech company which went bankrupt after yet another global financial crisis. They have now found jobs as workers at the Hofstadter&Co chain of convenience stores. The team was —and still is— Scrum certified, notably with the SAFe framework, but it blended the Agile methodology with a more classic project management approach. The team is solid: the one who used to be Product Owner is now the cashier. The one who used to be a Systems Engineer, now is the Chef. The one who used to be Project Manager, now is Sous Chef. The former mechanical engineer, software engineer and electrical engineer now are Chefs de Partie for bakery, meat and condiments respectively. You may ask, why so many people for a hot dog? Hofstadter&Co truly believes in growth as a way of making work more efficient: if a hot dog made by one person takes X amount of minutes, a hot dog made by a team of 6 will take X/6. The math checks out.

As soon as you walk into this dystopian store, you ask for your hot dog, but this time you feel something is definitely different. The cashier asks you to provide a User Story about the hot dog you want, following a strict, specific format, because otherwise —he assures— it won’t work. The format, he elaborates, goes like this: “As an X, I want a Y, so that Z. Then you timidly try: “…as a [customer], I want a [hot dog] so that [I can be less hungry]”. Great! Then the cashier comments that he will create a ticket in the system with the User Story for the team in the kitchen at the back. You suddenly remember you would like to add a soft drink to the order, but the cashier pushes back saying that, whoa, then the ticket will have to be turned into an Epic because it’s getting pretty complex. He asks if you really want that. Geez, you don’t really know but it sounds complicated, so you decide to drop the soft drink, and anyway your blood sugar levels have been a bit on the higher end lately. No soda then. Request is submitted, hopefully the food is coming. Fingers crossed. This is not so bad after all!

After some more waiting and uncomfortable silences with some inquisitive looks from you, the cashier picks up the phone and nervously discusses some inintelligible matters with someone and after hanging up he informs you that the system notifications were missed by the team in the kitchen because they had filters set up in their emails to make the notifications go directly to the trash bin. But, he enthusiastically comments that the issue has been solved now (ticket was retrieved from the dumpster in due time) so everything is ready for the “Hot Dog Kick Off Meeting” between him and the Chef, so he briefly leaves, leaving you somewhat puzzled. They don’t invite anyone else to this meeting, in a way they can agree on things without much hassle—i.e, consensus. During the meeting, the overall hot dog project is discussed, along with its scope and action items.

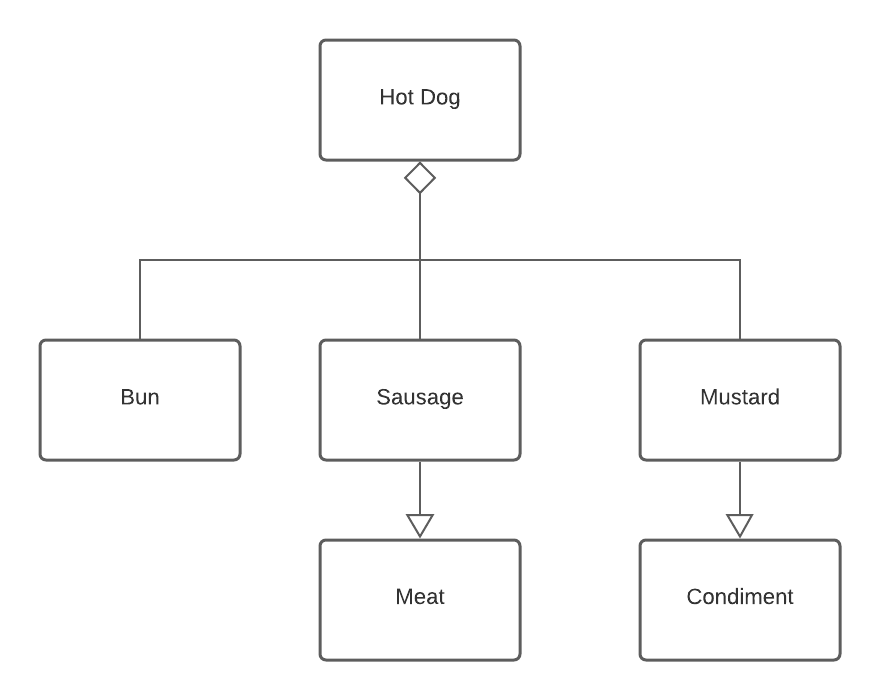

Meeting is done (took 1 hour, including initial 30 mins of smalltalk), so the Chef finally sits down and he is ready to design—note this is an unusually fast turnaround time only possible because the team uses Kanban and lean methodologies. Now, the Chef runs some feasibility analyses, seeking to answer crucial questions such as: can the hot dog be realistically done on budget and on time? Are all stakeholders' needs correctly understood and addressed? More importantly, he starts to model the hot dog in a specialized tool, coming up with a diagram which depicts how the different elements that make a hot dog form different relationships whose meaning is embedded in the graphical symbol at the tip of the arrows: an aggregation relationship and a generalization one —from more specialized classes such Sausage to more generic parent classes such as Meat and Condiment. Without this, the risks of someone not knowing what goes where nor what to do is unacceptably high.

Then, the Chef writes a Hot Dog Design Specification Document which is passed to the Sous Chef accordingly. At first the document is rejected because it has wrong Reference Documents (probably a copy paste issue). A second rejection takes place because the date was wrong. Third time’s the charm — it gets approved. The ball is rolling.

Now, unfortunately, since the Chef was not explicit on the behavior in the UML diagram above, the Sous Chef fills that gap by going freestyle —please always remember the diagram is not the model— so out of inexperience he interprets that the sausage must be slit and the bun put in the sausage. This misunderstanding can be explained by two facts: 1. The Chef is not collocated with the Sous Chef —it is a long stretch to stand up and walk the whole 3 meters to the Chef’s corner behind a door to ask 2. Cultural barriers may have played a part as well: they are from different neighborhoods in the same city, so the meaning of hot dog varies from block to block. The importance of communication.

Now, the Sous Chef goes and creates a hot dog Bill of Material (BoM), while you, the customer, start to question your life choices as you stare out the store window and see people passing by—they look so free and happy. You can only sigh.

Ok, then, the Sous Chef crafts a Gantt chart, with a set of important tasks, notably:

Gather raw materials from fridge

Hot Dog Assembly, Integration and Test (AIT)

Hot Dog Verification and Validation (V&V)

Overall Risk Assessment Process

His Gantt luckily includes critical insight: it shows that the sausages are at the critical path of the whole plan. And adds relevant milestones: Sausage Grilling Readiness Review (SGRR), Hot Dog Pre-Integration Review (HDPIR), etc. He also, luckily, performs a thorough Risk Assessment about the hot dog manufacturability—a risk assessment is a process to identify potential hazards and analyze what could happen if a such hazard occurs. Because he watched that video from Donald Rumsfeld, he is quite worried about the hot dog’s known unknowns and unknown unknowns.

With all this, the Sous Chef elicits the overly needed hot dog requirements, without which confusion would reign. These are duly captured in the Requirements Specification Document:

The Hot Dog shall be able to be consumed by both left handed and right handed customers

The Hot Dog shall consist on 1 bun inserted in the slit of a partially sliced sausage.

The Hot Dog shall be able to be packaged in a sheet of a paper which resembles an old newsletter but it’s not a real old newsletter.

Now, the Sous Chef sends all the documents to the Chefs de Partie, and calls for a meeting, which could’ve perfectly been an email, but—he knows—meetings are more effective, and people love meetings. During such meeting, one of them, the Meat responsible, points out there seems to be something odd with the requirements. He expresses he has seen hot dogs being the other way around, this is, a partially sliced bun hosting a sausage. The discussion goes on for a long extent until the team decides to escalate this back to the Chef. The Chef happens to be currently reading the 538 pages of the Business Process Modeling Notation standard (the next fad he is planning to embrace full on), so he’s a bit upset he’s been bothered by this. First he thinks, damn, can’t people be proactive and solve issues themselves? But then he quickly remembers he’s the only Six Sigma Black Belt in the team so it makes sense they come to him. As he’s summoned, and after reminding everyone he is the most experienced person in the room and that he’s seen enough hot dogs throughout his life, he declares the design is to specs—engineering jargon for ‘rock solid’—so the Change Request is archived. The project moves into phase C, which the cashier—who is back at the counter—proudly informs you of, although you have literally no clue what that means.

Things now go like a rollercoaster. The Meat responsible gets the sausage ready, the sausage is slit, and the responsible of bakery is more than set with a freshly baked bun. The team proceeds to assemble and integrate the parts. The sausage-bun tandem easily comes together, bun slides comfortably inside the sausage. As the condiment comes in, a state-of-the-art, cutting edge hot dog is born. A post-integration review takes place, with very minor non-conformances. Now the team runs the Verification Procedure—this means, to check if the assembled product complies with the requirements. It checks out. Hot dog is go; ready to ship. The team prepares the paperwork. The Chef signs the docs and hands the product over to the cashier, and the cashier is now ready to do the handover to the customer, all according to the procedures. After all, you can see why there’s a shiny ISO 9001 seal on the store’s window. The team dreams on eventually reaching CMMI level 5 (optimizing) in hot dog making, but for now it has to conform itself with a modest yet respectable level 3.

It’s been forever since you entered the Hofstadter&Co convenience store and became a hostage of your own unfulfilled needs—but hey, quality takes time. When you see the long-awaited Frankfurter approaching, you feel nothing but desperate happiness. Little you care about the fact the whole thing has been prepared the opposite way as common sense dictates. The cashier asks you: “we know we made the hot dog right, but did we make the right hot dog for you?.” As you only care about finding the exit while promising to yourself to never ever come back under any possible circumstance, you nervously acknowledge. Delighted by that awesome feeling of work being done, he mumbles:

—There it goes, another happy customer.