Plug & Pray

“Just remember: it’s not a lie, if YOU believe it “ — George Costanza

When an engineer tells you that something they just made is “plug&play”, most likely this person is lying to you.

A white lie, maybe, but a lie at last.

Early computer peripheral devices required the end user physically to cut wires and solder together others in order to make configuration changes. Such changes were intended to be largely permanent for the life of the hardware.

To make computers more accessible to the general public—euphemism for making them more marketable in broader audiences—it required making the configuration of peripherals as intuitive—euphemism for baka yoke—as possible. The idea was straightforward: there are people out there who can barely manage to turn on the TV, let alone handle a soldering iron at more than 300 degrees celsius. How do we sell stuff to these clueless neophytes?

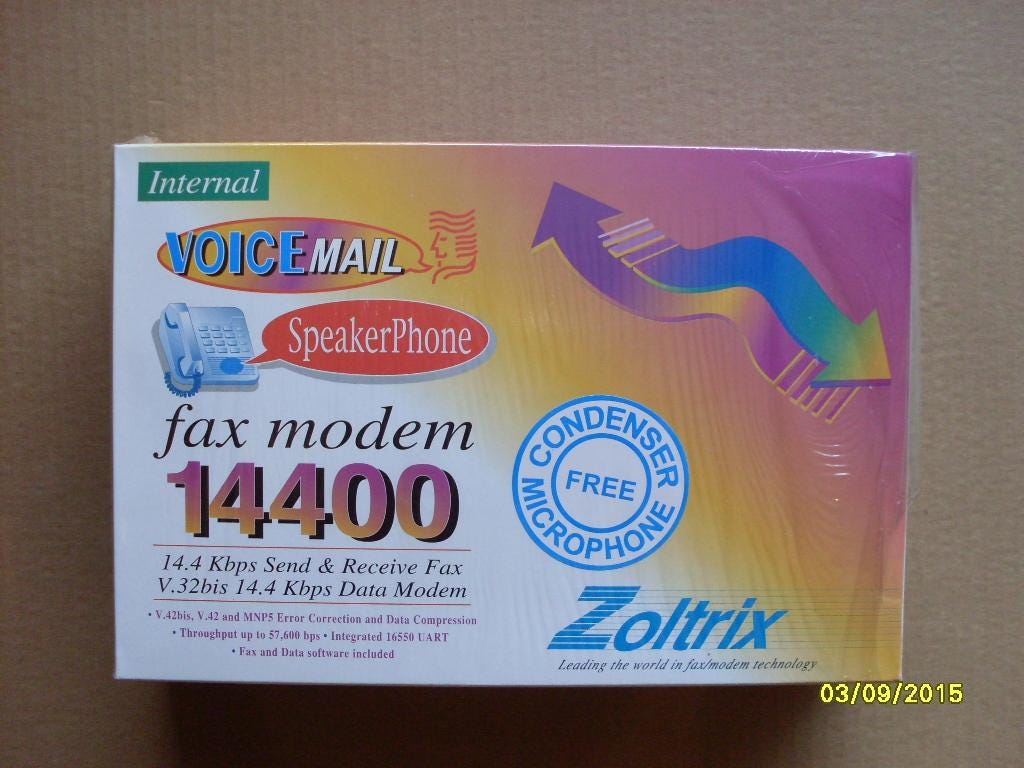

First attempts were the good old jumpers and DIP switches. My 14400-baud Zoltrix modem I used ad nauseam for connecting to BBSs thirty years ago had both.

All this still required thoroughly reading manuals. So, decent text comprehension and even some language skills—if the manual was written in a foreign language—were necessary. What is more, adding peripherals required unscrewing and opening the lid of your computer and mechanically connecting things in PCI or ISA slots in the motherboard, previously cleaning industrial loads of dust and dead flies. Also, any new hardware device landing in a computer needed a driver, this is, a piece of software “magic” to make sure that the inner workings of the new “thing” would couple in a non-traumatic way with the rest of the existing system.

The motivation was plausible. Why would an accountant want to shove boards in a PCI slot, tweak a DIP switch with a screwdriver and deal with drivers when all he wanted was to calculate tax returns in a spreadsheet? Why on earth would Mr Blonde from Reservoir Dogs have to read the manual of a sound card and figure out things like sample rate if all he wanted was to play “Stuck in the middle with you” in Winamp for a little dance?

A relationship was increasingly coming under the spotlight: the relationship between the end user of a computing system and the knowledge needed to operate it. This tension went in a couple directions: first, computers becoming more functionally “integral”: for example laptops gaining traction by being one cohesive piece altogether, requiring less tampering and DIY screwdriving. And second, decreasing the variety of interfaces left available to the user: the less amount of holes left open for a user to mess things up, the better. In time, parallel ports, serial ports, VGA ports, they all disappeared. I write these lines from an anodyne laptop which has only 4 USB-C connectors to the outside world, plus a lonely 3.5mm audio jack that stoically resists as the last relic of a bygone age. Anyway, things evolved to the point where users are able to plug a tiny flash drive in and the computer manages to recognize it regardless of its manufacturer, chipset or internal design. Which makes lots of sense. Now, this technological feat was the result of massive market pressures for vendors of all kinds to consolidate and adopt standardized interfaces and protocols so they could keep on doing business. If there was a stubborn vendor sticking to RS232, they are surely out of business by now.

The downside of the plug&play concept is that it spread a mindset of “black boxes magically mating to other black boxes”. Plug&play was possible only after a wild, ruthless standardization and consolidation of too many things happened, and happened fast.

Thus, the plug&play mantra colonized the minds of many in the engineering scene, radiating a wave of blissful oversimplification across the board. All in the name of that somewhat bastardized term: abstraction. This is, for the—a priori noble—cause of “hiding complexity”.

Hide it as much as you want, but complexity ain’t going anywhere, anytime soon.

The evergreen observational law of “conservation of complexity” coined by Larry Tesler captures the idea: “The total complexity of a system is constant. If you make a person’s interaction simpler, the hidden complexity behind the scene increases. Make one part of the system simpler, and the rest of the system gets more complex.”

Design and development of complex and mission-critical systems rarely benefits from wishfully thinking that simplicity in interfacing A with B goes unpaid, and that it happens thanks to the fairies. Unless A and B went long extents to agree the way to talk to each other beforehand—in a way that just hooking them together would be necessary for the magic to happen—making them work properly will require RTFM.

Next time a fellow engineer tells you that they made you something “plug&play”, you better ask where did the complexity go before you find out by yourself down the road, in the most unglamorous way possible.

Clowns to the left of me,

Jokers to the right,

Here I am stuck in the middle with you