The Making of a Socially Awkward Engineer

Engineers are typically considered “socially awkward”. At least that seems to be the general opinion, most likely originated from non engineering frames of reference. Some tend to find working with engineers to some degree difficult. We engineers have a language and thought process that is quite particular and intricate and, in some cases, it can baffle the heck out of non engineering people. Without trying to picture us as special snowflakes, we definitely are a particular bunch. But, for the sake of avoiding—for once—falling into over-generalizations, I will today speak for myself, and how such “social awkwardness” might have formed.

In my particular case, I haven’t been socially awkward all my life. I mean, without having been the clown of the party, I could say my childhood was pretty ok, socially speaking: friends, football, music. More or less the usual. By the moment I started working—I was 21, while studying EE at the same time—I was equipped with the basic tools to socially engage at the workplace, or so I thought.

But 20 years through many, many different workplace atmospheres took some toll. Small companies, big companies, more homogenous, less homogeneous, more international, less international. Family businesses, multinational corporations, startups, state owned organizations. In my home country or abroad. I’ve seen a lot, and that lot has definitely formatted me. And as Madame Stael is believed to have said:

“The more I see of men, the more I like dogs.”

When I started, I was really into it. You know, getting to know people, sharing jokes, how was your weekend, how this, how that. Hanging out with the office folks. Lots of small talk but also a genuine curiosity about how others were doing, what they liked, etc.

My first social questions started with company parties. Initially, I thought: ok, why not, we celebrate some accomplishments, the end of the year, whatever. Bosses will be there, yikes, but who cares, we eat something, we have fun, then I go home. But in reality, I would stand there, drink in hand, seeing Pedro from Accounting doing the limbo dance at the sound of Venus from Bananarama, tie in the head—rambo-style, all sweaty, screaming unintelligible things. I would look around and all of a sudden, most of my colleagues would have turned into Ibiza disco-goers.

Ok, what’s going on?

I started to see that, for some of my workmates, whether you were a colleague or a partner for a lambada-train largely depended on the amount of margaritas consumed. And it’s not that I didn’t drink at all and I only pointed the finger to sinful party-animals who were just having fun. I can have a drink, been there done that, but no amount of tequila can change the fact Pedro the Accountant will always be Pedro the Accountant to me. The most unsettling part? The Mondays after these parties were quite odd for me, although everyone was acting like nothing had happened, except for Pedro who, of course, would call in sick.

Then, and as it happens to many engineers around the world, my career took me into managerial waters, and the managerial waters are very socially demanding waters. As a manager, you find yourself leading people, so you are supposed to, well, get along, motivate and guide them. You have to speak to various audiences, you must sound witty, inspirational, confident. So, here was the puzzle for this engineer-turned-manager: the sudden need to grow a hyper-mature social and emotional zen-like intelligence out of nowhere. Moreover, if you hit the “jackpot” and you did this transition in a young company where the HR department is minimal, or at least not something you would call precisely mature, you are left alone with the elements when it comes to dealing with people's issues. Turns out: people have a lot of issues. Insecurities, unmet career expectations, egos, jealousies, mistrust, tragedies, and many other things.

At one point I was dealing with Kirchoff Laws, soldering irons, and interrupt handlers. Next, I was listening to someone telling me the utter importance of having the word “Senior” before his title. His age? 24 tops.

Sigh.

How do you grow a zen attitude in such a short time? You don’t. You just survive as you try to understand what the hell is going on. The most naive suggestion I’ve heard to face this were those expensive and vacuous coaching courses, as if they would be the magical answer. I mean, they can help to some extent, but you can’t rely on powerpoint slides when someone is opening up to you because they feel miserable. You can’t just throw the platitudes those coaches spout, hand in chin: “tell me, what makes you feel like this? “You gotta believe in yourself Loretta, but no, you won’t get the raise, now please evacuate”. Powerpoint coaches do not really know what managing really means. Nor do I. But there’s a non glamorous side of managing that requires lots of listening, understanding people’s fears and worries, and then—perhaps most importantly—doing something about it. You can’t learn that from powerpoint as you can’t learn to play the ukulele by powerpoint.

But, fair is to say, people’s fears and worries might vary a lot. Once, someone came to my desk with a very worried face and said “I need to talk to you asap”. I—a forming manager trying to learn to gauge body language after watching a few episodes of Lie To Me—saw a genuine expression of concern, so I thought: heck, this guy is leaving or having some serious issue. He booked a meeting, and with the same funeral face, he said: “my laptop is very heavy, I need a lighter laptop”.

Infatuations and soap-opera-grade romantic shenanigans in the office are particularly hard for me to grasp. I mean, sure, make love not war, whatever. But the amount of adults confusing their workplaces with a high school is staggering. Many years ago, a manager of a full division organized a surprise birthday party for the secretary he was infatuated with. He dead-seriously moved hundreds of people to the company’s cantine to lurk behind some wall to astonish this woman. I could see the cringe in my poor boss’ eyes as he was forced to come and politely ask us to leave our offices and join the crowd. I managed to stay in my office in silent protest, thinking: this just can’t be happening. Years later, I coincidentally shared office space with this unfortunate woman and she commented on how much that thing kind of ruined her existence because everybody started to think she had special privileges, and how much she hated herself after that.

No wonder, emotions are always present in the office space.

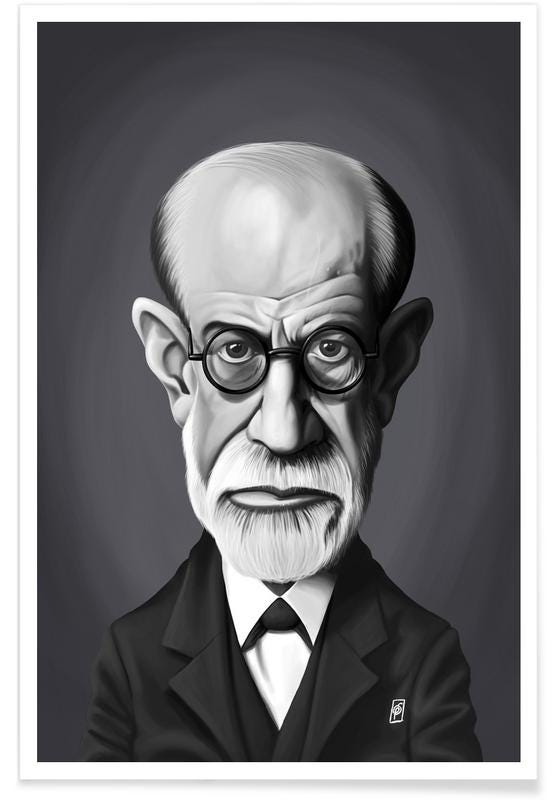

There was this time when two team members had a fight. It happens. So I went to HR for some guidance. HR departments have this tendency of looking like they really, truly care although you can see their eyes are dead. So, they suggested a psychologist to decompress. I said, alright, why not. Psychologist was summoned some time after. He looked more like a backpacker than a psychologist, but well, looks can mislead, and I don’t know what I was expecting. Turns out, the belligerents refused to talk to him—it was not mandatory, I learned—so I ended up having to entertain the psychologist for an eternal while, as he was trying to analyze me instead. He was a psychoanalyst, so I kind of knew the diagnosis beforehand.

There have also been unethical, if not illegal twists. For example, eons ago this ex-boss of mine asked me to help him install a keylogger to some (female) employee’s computer he suspected was sharing “trade secrets” with a competitor (his overcomplicated choice for dissimulating he was inappropriately interested in this person). Tell me about GDPR. Of course I refused. Shortly after, this female employee came to the IT guy—who was sitting next to me—complaining that her computer was “acting weird”, tildes not working, etc. Without fully opening up—because I had no strong evidence a keylogger was ever installed—I convinced the IT dude to change the poor woman’s laptop for good. Why on earth was I dragged into all that? The more I saw of all those things, the more I wanted to hug my oscilloscope.

As I grew older, a part of me started to crave for more distance from all this intense workplace social dynamics. Lunchtime started to be a good place to commence, so I began shifting my lunch time to hours a few standard deviations away from the popular times. Cannot say it was something entirely deliberate, but it felt like a good place to start taking some air, eat in peace, think, read. And this worked pretty nicely. But, in this particular company where I started such practice, the late lunch schedule weirdly aligned with this company’s very senior management lunch schedule. So I would often find myself involuntarily sitting with these highly accomplished 70+ mad scientists who were not precisely busy and would not stop talking about topics such as cold fusion. It was not a big deal, and it was occasionally fun, except that, from time to time, one of them would randomly turn to me and ask: “and what do you think?” Ehh…

There can be many types of “social awkwardness”. The current pandemic might have changed a bit the way we interact with our colleagues, for the good or for the worse. Hopefully—and I never thought I would say this—things will soon fully go back to normal and we will get to see again the accountant doing the Macarena. Being socially awkward can be problematic for some people who may feel rejected, neglected, failing to connect, etc. None of that is what I am talking about here. I am talking about the comfortable, willing transition from an initially socially eager person into someone who enjoys a nice, safe air gap or “moat” from the daily office happenings. Not all engineers traverse through the same path, many will probably choose joining the lambada train and be party animals, or coffee machine richmeisters. Good for them.

My particular path has been guided by always remembering that the workplace is not a prom, and that we get paid to get shit done.