The Framework

Your company is a mess. You grew from 20 to 200 people in, say, 3 years, and things are out of control. What used to be a tight, responsive, highly motivated group of people getting shit done has become an amorphous army of middle managers with no authority, no clue what they’re doing and only reacting to cover their own bottoms. Industrial loads of improvised, loosely enforced bureaucratic short-lived experiments bloom. There is a growing sense of desolation. Turnover increases. What the hell is going on?

Then, in your desperation, someone recommends you a consultant. “He helped X company scale, this is the guy you need”. Consultant comes along flying business and only after arranging the details of his paycheck, he spouts in a presentation:

— I know what your problem is. You are undergoing phase 4 in Greiner's Growth Model.

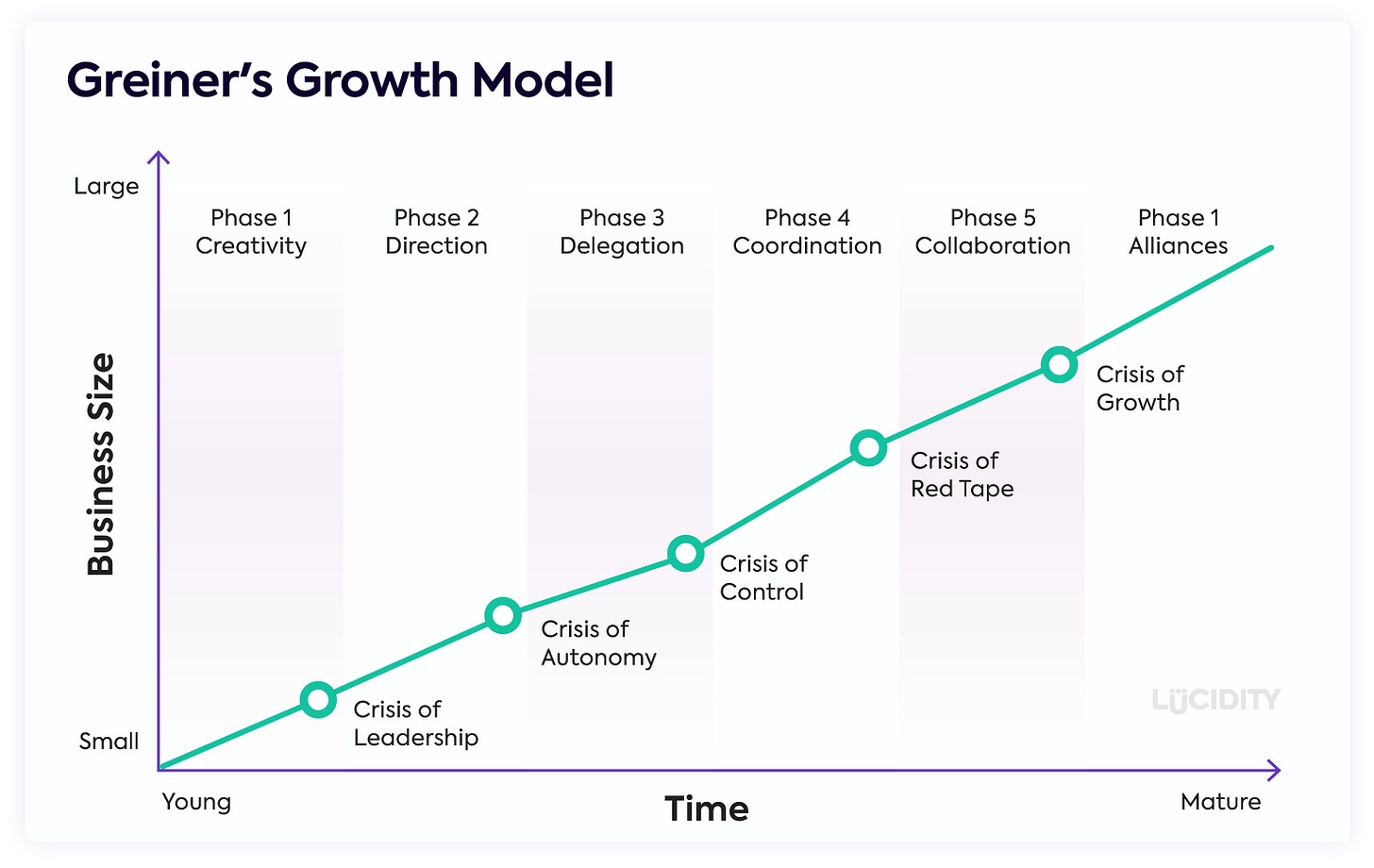

For context, Greiner's Growth Model is a framework—this term is key in this article—that supposedly shows the different phases a company goes through to achieve growth and the different types of crisis that may occur during those. One key factor for these kinds of platitudes to be swallowed more easily is to have a slick graphical depiction. Greiner’s model is no exception. See below.

Framework says that, as you grow, you undergo 5 phases: creativity, direction, delegation, coordination, collaboration, with an extra phase called “alliances”, whatever that means. What marks the transition between phases are “crises” called: crisis of leadership, autonomy, control, red tape, growth.

The problem with these “models” is the suggested artificial discretization you will never find in any social system. Social constructs evolve in continuous time, and crises are impossible to be labeled, packaged, nor predicted this way. Some might say I am treating all this too literally, but it is precisely the problem I am coming to comment about: many decision-makers take these things as literally as I am taking it at the moment, but they do worse: they modify their decision making process influenced by such “models”, and they compress serious stuff under labels such as “a crisis of autonomy”. A “crisis of autonomy” most likely means real people having a miserable time, burning out and dreading going to work every morning. Instead of looking at a chart in a slide written by someone you just met, maybe better go out and do something for those you’ve known for years? No?

The increasing tendency to embrace oversimplified models for their own sake is doing a disservice to the otherwise great endeavor of building great organizations: organizations where common sense prevails and it’s fun and satisfying to work for. This trend is the result of the proliferation of experts cashing in with “methods” canned for higher-ups to consume like instant soups as a mechanism to evade reality, losing connection to what is happening down at the trenches.