If Startups Were The Beatles

In my never ending quest of finding analogies between disparate things in life, today’s is perhaps the least far-fetched of them all, although it might read otherwise. Startups and music bands have many parallels, some of them almost obvious: they’re a small group of people trying to make it. Both in startups and bands, only a small few finally make it—making it understood as biting a consistent, significant piece of the market and becoming a household name in an industry or genre. Making it *not* understood as becoming unicorns, nor one-hit wonders, as these adjectives are seldom an indication of anything tangible.

I wouldn’t be lying if I said that The Beatles1 are perhaps the most influential band of all time. Four guys out of Liverpool who shook the world by means of catchy songs, silky harmonies and, more importantly, a constant push of their boundaries. When it comes to The Beatles, there was the music, but there was also the massive, collective hysteria these folks unlocked in a western world which was still recovering from the horrors of WWII; a world which was still quite sanctimonious and repressed, a world where cultural movements came to act as venting valves.

The Fab Four were composed of two creative powerhouses like John and Paul, a “hidden champion” like George, and, well, Ringo. The latter being sort of the rug that ties the room together, who was not the best drummer in the world —a quote misattributed to John Lennon states Ringo was not even the best drummer in the Beatles— but indeed was a source of inspiration2 and a bridge between ballooning egos fed by industrial loads of hype. The Beatles lasted roughly 10 years. Ten intense and vertiginous years where a whole lot happened. Similar lifespan to these meteoric companies which are born in coffee shops or universities and explosively expand to become global corporations. In both cases, young people rapidly going from beggar to riches. And in some cases, fame.

In every young startup, there are different talents in the “core” team. There are Johns and Pauls, who bring creativity and ideas, who can play different instruments (wear different hats) and who get along —at least initially— very well, forming tight, creative small societies. There are quiet Georges who make great contributions but usually get sidelined, and there are Ringos, who are technically rudimentary but essential as team bonding factors and —a very important function— as psychological and even comedic relief when things get ugly.

In the Please Please Me stage, startups are simplistic and naïve. Their narratives are shallow and purposely effectist, parroted ad nauseam. Strategies are all about getting hype, and about mimicking what others do. There is little effort in finding further meaning, given the current “melodies” seem to be effective so it’s also about milking it and rolling with it. But as this superficial phase goes all the way through the stages of With the Beatles, A Hard Day’s Night, Beatles for Sale and Help!, the amount of imitation eventually wanes, and the startup’s true “sound” starts to surface. Products and ideas of the like of Norwegian Wood and Yesterday hint there’s a drive to explore new territories and a more mature use of words, instruments and chords without fully divorcing from the past. Those who don’t show such potential are bound to perish singing Twist and Shout.

Like bands, talented startups show their true colors when they play “live” or go spontaneous: pitches, conferences, random encounters. They show a consistent, charismatic and confident message, regardless the conditions, keeping the audience wanting more. See these four guys from Liverpool playing live with overly rudimentary amplification at the Shea Stadium in 1965 with tens of thousands of people screaming their lungs out and still performing with a quality which most modern bands with state-of-the-art technology couldn’t dream of. You want that concert to last 10 hours if possible.

And then there’s what we can call a “Doctor Robert” moment.

John Riley was a dentist acquaintance of John and Cynthia Lennon, George Harrison and the latter's wife, Pattie Boyd. At a dinner party attended by Lennon and Harrison and their partners in March 1965, Riley laced their coffee with LSD, providing the two Beatles with their first experience of the drug, which some mark as a before and an after for the band. Without implying a startup tipping point depends on the consumption of hallucinogenic drugs (we might need some research there), there is a moment where founders and core members must realize there is something else than talking about democratizing X or Y, or becoming the Uber or Apple of Z — the equivalent of singing about girls, broken hearts and rock and roll. Smart founders realize playing what others are playing is okay but will not make the thing genuinely ignite. They stop looking to their sides, and start to only look forward because they are now forming the path ahead. For The Beatles, the LSD acted as the trigger, although the talent was definitely there. For startups, the trigger can be anything, as long as it happens and it makes the team want to puncture the boundaries one way or another. The sound needs to change and become unique.

With all that in place, then comes the Rubber Soul and Revolver stage. Here, the group is “in the zone”. Riding still on some hype, but channelizing the attention with better products and focus, better narratives, a unique tone and proposition. As things go faster, egos can start growing beyond limits and what used to be pure camaraderie and joy gives way to low-key reservations. At this point, there can be some existential crisis stemming from some sort of flywheel effect, which can be perceived in Magical Mystery Tour and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band —with the exception of A Day in the Life which remains a rustproof masterpiece. At this stage, everyone is fixing holes and wondering who is the Walrus.

I am he as you are he as you are me

And we are all together

By this time, The Beatles were overly rich3 and massively famous, which didn’t come without its dose of existential crisis. So they took a trip to India for some transcendental meditation —with some odd consequences— but at the same time producing raw acoustic gems which would eventually become part of the The Beatles album, also known as The White Album. Although the seed of disbandment might have already been sown by then, this album comes to show there can still be creativity in conflict as well.

Then, the Yellow Submarine, Abbey Road and Let it Be stage marks a phase of decline and decadence. Peripheral actors grow more and more influential —the Yoko Onos4 of the organization such as consultants, coaches and/or newly appointed VPs coming from who-knows-where. And charlatans proliferate.

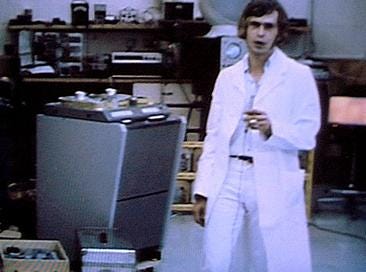

Somewhere between 1965 or 1966, while checking out an art exhibit at the Indica Gallery, John Lennon became enamored with a man who had recently moved to London from Greece. He claimed to be an electrical engineer. His life before moving to London was —and still remains— unknown. But from that meeting onwards, Yannis Alexis Mardas became known as “Magic Alex.” Alex, when asked, described himself as thus: “I’m a rock gardener, and now I’m doing electronics. Maybe next year, I make films or poems. I have no formal training in any of these, but this is irrelevant.” Such self-description would match almost word by word most consultants out there if they could only describe themselves in such honest way as Alex did. You can’t say he was trying to scam anyone.

Magic Alex’s electrical gadgets and contagious enthusiasm caused him to become a part of the Beatles’ inner circle right up to the last days of the band, and for the longest time, they trusted his every word. His ideas were revolutionary, after all. Wallpaper that could act as loudspeakers. A recording studio with multiple computers and a 72-track desk. Mardas gave the Beatles regular reports of his progress on the 72-track thing, but when they required their new studio in January 1969, during the Get Back project that became Let It Be, they discovered an unusable studio: no 72-track tape deck (Mardas had reduced it to 16 tracks), no soundproofing, not even a patchbay to run the wiring between the control room and the 16 speakers that Mardas had fixed to the walls. The only new piece of sound equipment present was a crude mixing console which Mardas had built, which looked (in the words of George Martin's assistant, Dave Harries) like "bits of wood and an old oscilloscope". The console was scrapped after just one session. George Harrison said it was "chaos", and that they had to "rip it all out and start again, calling it "the biggest disaster of all time56."

If anything, Magic Alex’s raging incompetence left a great legacy: a phrase added to the English scientific language known as the ‘Mardas Gap’, which is used to describe the disparity between a designer's promise and what that designer can achieve. A term I personally use extensively, both as designer and as customer.

By now, the corporate matters have taken over any creative or innovative work. The members of the core team, now looking increasingly disheveled and acting like they could not care any less, become more and more apart from each other. At this stage, turtlenecks are profusely wore, and abominations such as The Ballad of John and Yoko or Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da or similar products get absentmindedly approved.

If left unattended, eventually every startup meets its April, 1970 or lives long enough to become a traveling tribute of themselves like The Rolling Stones.

Note for all those early stage startup founders out there. Whenever a visionary VC turns down your startup idea, remember someone turned down the Beatles because “guitar groups are on the way out.”

There has been quite some debate about the opening chord of “A Hard Day’s Night” that it has its own section in a Wikipedia article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Hard_Day%27s_Night_(song)#Opening_chord

They were creating so much revenue some accounts say they saved the British pound from a crisis.

There is this common belief that Yoko Ono is the main reason behind the disbanding of the Beatles. This claim speaks as highly misogynistic. As if four grown-up men were having the time of their lives until this shady woman came along to ruin everything. I do not subscribe to that, as it is just plain scapegoating. On the same lines, consultants and randomly enthroned VPs cannot be always fully blamed for organizational collapse. Those who do not call their bullshit out can.

From The Beatles: the biography by Bob Spitz.