Uncommon Sense, Common Nonsense

How many times have you been in a meeting where a higher up or a manager said or proposed something which made you internally shout: “that makes no sense”, and you looked around for others to be as outraged as you were only to find that everyone around the table was nodding in agreement as if the rubbish this person just spat was the best idea that has ever seen the light of the day?

Astatine, with atomic number 85 and atomic weight 210, is the rarest element on the planet. Approximately 1 gram of such material exists on the whole surface of the Earth at any given time, whereas only 50mg of it have ever been produced, mainly for nuclear medicine.

The list of the planet’s rarest materials is surprisingly missing one element which is, despite its misleading name, even rarer: common sense.

Common sense is a very strange thing. It is not explicitly taught in schools or at home. Parents don’t usually sit with their kids and have “the talk” about it. We cannot easily define it in an unambiguous way.

In 1964, the United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart was trying to describe his threshold test for obscenity when Ohio was trying to ban the showing of the Louis Malle film The Lovers (Les Amants), which the state had deemed obscene. In explaining why the material at issue in the case was not obscene and therefore was protected speech that could not be censored, Stewart wrote:

I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description ["hard-core explicit material"], and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that.

It similarly applies to common sense. We know it when we see it. Or, especially, we almost physically know it when we do not see it: A sort of an internal scream, a rush of blood to the brain which may even contract your facial muscles involuntarily in distaste.

The cold definition states that common sense are the beliefs or propositions that most people consider prudent and of sound judgment, without needing any esoteric knowledge or specific study or research, but based upon what they see as knowledge held by people in common. Common sense is the ability to think logically without the need of using specialized or advanced knowledge. There’s “street” common sense, and there is more domain-specific common sense. Street common sense is pretty straightforward. For example, if you are robbing a bank, you are most likely not leaving your name and address to the cashier when you pass the robbery note. You don’t need a PhD to know that, and I bet you cannot remember when you learned that broadcasting personal details is not a great idea when you are a criminal.

Engineering, or more generally domain-specific common sense, is harder to identify.

Years ago, the management of a company realized work had to be better organized and prioritized. Who doesn’t want that, right? The system proposed resulted to be team oriented, this means, team A had its own list of tasks with priorities defined by that team supervisor’s criteria or taste. Same for team B, C and D. Now, because projects—which statistically tend to pay the bills—and each team’s tasks were not mapped together, and moreover because task dependencies between teams were not considered either, it ended up in a clusterfuck plagued with priority inversion. It made no sense. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the reaction to the problem came rather quickly and it followed the expected rationale: add a tool to deal with the FUBAR1.

Life should teach managers that projects pull tasks, dependencies and cross-team interactions together, and not the other way around. No one would let plumbers, electricians and bricklayers alone siloing their way while building a house. If it’s common sense for the latter, why is it not for the former?

On one occasion, a company I worked for wanted to launch a new product: a queuing management system of sorts. You know, those things you face when you go to the doctor or similar: you press a button, it assigns and prints you a number, you wait until you hear a dingdong, you get visually cued which server number to go, you are finally served. Project started rather small and with rather simple requirements, so we thought of using LED 7-segment big digits—an existing product—and a very simple user interface with one button connected to a controller. The engineering team had initially selected a tiny 16-bit microcontroller for managing the whole thing, which seemed more than enough for the task—it was cheap, power efficient, etc. But management called for a meeting. In a long presentation, our boss listed the new “features” he wanted: add the possibility of optimizing the queue. Add the capability of collecting statistics on who is the slowest server. Add the chance to select different dingdong sounds. Add the possibility of choosing different fonts for the printed ticket (for the visually impaired), add the possibility of supporting a variety of printer technologies. It became clear that doing all that on top of such a humble architecture had become a bit, say, far fetched. As much as this may sound like specialized knowledge and as the manager may appear as a poor victim of his inexperience, it is nothing of that. It’s plain common sense (or lack thereof): you can’t stretch the requirements of a system like plasticine and expect some magic elves will ensure the underlying architectures will adapt, like in that fairy tale where those elves help a poor shoemaker during the night. All this applies exactly the same if you talk about a queuing system or a nuclear submarine. We solved the queuing thingy without calling any elves but with a PC, some Visual C++ —mind it was 2007— and a flat screen. Customers were able to choose fart sounds as dingdong if they wanted.

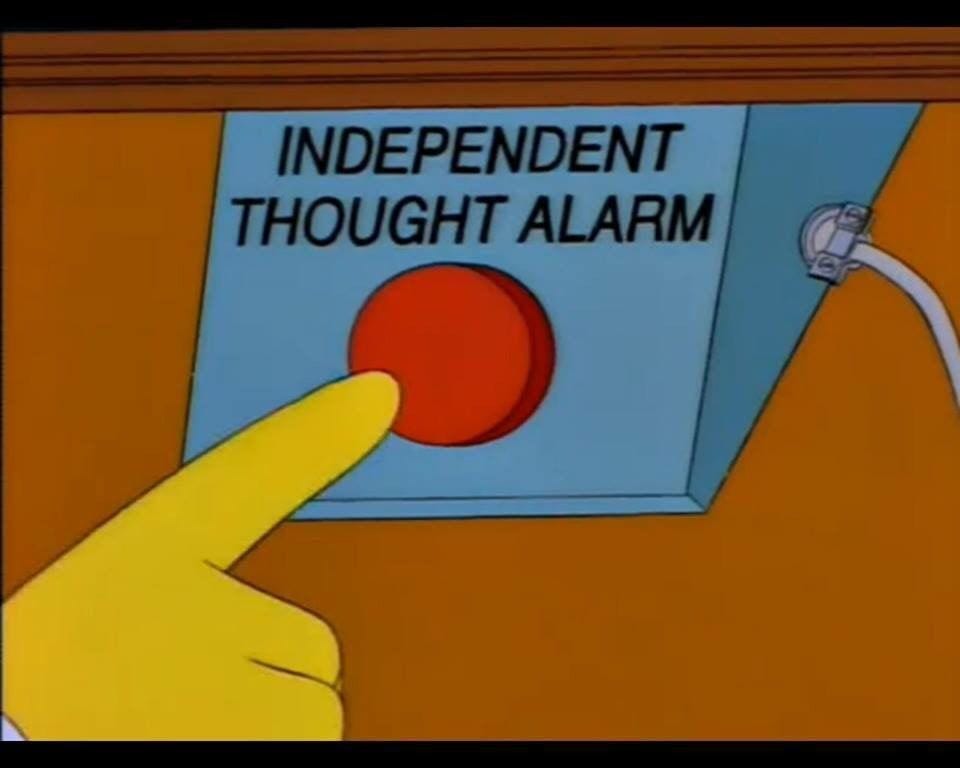

You would expect senior colleagues to be equipped with a higher dose of common sense compared to more junior people. This tends to be statistically the case, but as with any population and distribution, there are outliers. There can be nonsensical oldtimers, and young people with well-grounded common sense. And, more importantly, the ubiquitous power of boot-licking and self-preservation may increase the gap between what some think vs what they say. Someone supplied with a solid dosage of common sense could choose to play dumb and applaud nonsense like a seal in order to conserve their position. Sadly, independent thought might be punished. We live in strange times.

There’s a phrase that goes: it is only common sense if everybody knows the answer. Perhaps the task for all of us is to help spread domain-specific common sense more effectively so it becomes known by everybody. And, whenever possible, choose places to work where calling out nonsense is rewarded and encouraged.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_military_slang_terms#FUBAR