When All You Have is a Hammer

I mentioned in a previous article1 how damaging a wrong and over-confident boss can be, and how little leverage subordinates have for telling the boss that they are about to (sometimes literally) crash the plane. But, I disliked the idea of higher-ups as endlessly powerful creatures capable of ruling powerless masses, so I zoomed out in the analysis until I got to the point where a question popped up: if a subordinate is most of the times incapable of calling out an executive, then, who can? Who tells the emperor that he is wearing nothing? We will get into that. First, a bit of context.

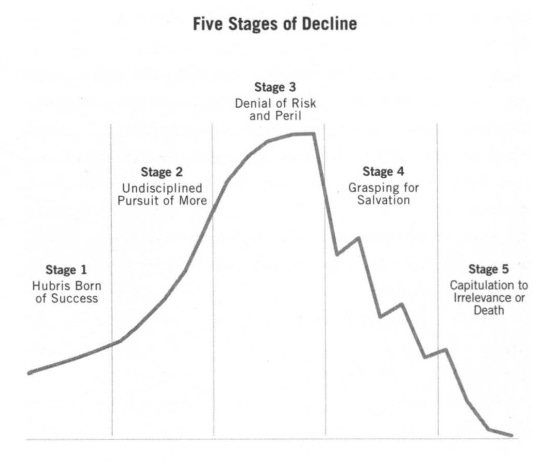

Jim Collins2 has written extensively about the rise and fall of companies. In his “How the Mighty Fall: And Why Some Companies Never Give In”, he and his research team explain that companies tend to decline following five stages:

Hubris Born of Success: This stage kicks in when people become arrogant, regarding success virtually as an entitlement, and they lose sight of the true underlying factors that created success in the first place, ignoring that chance plays a role in many successful outcomes, and failing to acknowledge the role luck may have played in their success and thereby overestimating their own merit and capabilities.

Undisciplined Pursuit of More: The nefarious “more is more” stage. More scale, more growth, more acclaim, more hype, more of whatever those in power see as "success". The organization grows beyond its ability to fill its key seats with the right people, and it balloons staffed with the wrong people.

Denial of Risk and Peril: Internal warning signs begin to mount, yet external results remain strong enough to "explain away" disturbing data or to suggest that the difficulties are "temporary" or "cyclic" or "not that bad," and "nothing is fundamentally wrong."

Grasping for Salvation: The cumulative risks-gone-bad of Stage 3 assert themselves, throwing the enterprise into a sharp decline visible to all. Here’s when "saviors" and charismatic visionary leaders may appear, with bold but untested strategies, or a radical transformation, a dramatic cultural revolution, a hoped-for blockbuster product, a "game changing" acquisition, or any number of other silver-bullet solutions.

Capitulation to Irrelevance: The longer a company remains in Stage 4, repeatedly grasping for silver bullets, the more likely it will spiral downward. In Stage 5, accumulated setbacks and expensive false starts erode financial strength and individual spirit to such an extent that leaders abandon all hope of building a great future. The organization atrophies into utter insignificance; and in the most extreme cases, the enterprise simply dies outright.

Graphically, it looks like this:

The book dissects different case studies of resonant companies which went from great to near collapse in an almost unstoppable death march. But it also shows how, in some cases, companies recovered just in time. Company decline is, luckily, not an irreversible process.

Collins’ book mostly talks about public-traded, multi-billion, high-profile industry behemoths and puts a particular emphasis on CEOs and their mistakes, which is a somewhat easy thing to do if you have the benefit of hindsight, which is usually 20/20. But it falls short on shedding light on the real problem: the corporate governance flaws which gave CEOs enough freedom to make the mistakes they made, by spasmodically ousting executives and replacing them with charismatic charlatans, or by approving mergers which ended up being deadly ballasts3.

After reading How the Mighty Fall, you may get the impression CEOs are the ones to blame. And you would be right, but that is only one side of the story. How does corporate governance prevent a powerful CEO from taking a company all the way from stage 1 to stage 5? The mechanism of choice to prevent such a pilgrimage into the abyss is an entity which tends to cleverly dodge the spotlight: the Board of Directors4. What are the Boards of Directors and how did they appear?

Once upon a time, companies were mostly owned by families and individuals. But then we, as the inventive and restless bunch we are, had the marvelous idea of inventing what now is known as the modern corporation, by means of subdividing company ownership into small chunks (shares) which could be sold and traded by basically anyone. The concept picked up and soon people were investing in corporations with very little liability. This came with an uncomfortable side: companies started to be owned by thousands of people. And this made corporate governance a pain in the neck. Mostly because those owning stock felt entitled to have a say in the company decisions, and wanted to be informed. Meetings with shareholders became chaotic: everyone had questions, debates would go forever, decision-making became impossible. So everyone started to hate these meetings. The solution at the time? Meet all at once, but less frequently, like once per year. This approach had a downside: it made shareholders gossip extensively during the time in between the meetings. Rumors would spread without control. It again called for a solution, and the solution was: the Board. And it was pretty good for the problem it came to solve. With shareholders being able to choose board members they trusted, these board members could act for the best interest of those owning stock. And management loved it, because in a way, the Board acted as an abstraction and insulation layer between them and the needy, noisy shareholders. But, when it came to strategic thinking, problem solving and, more fundamentally, keeping wacko executives at bay, Boards were not as great.

And then, if this was not enough fun, another invention came along to make things more interesting: the tech startup.

The tech startup is a product of modern venture capital. And venture capital appeared in the 40s, following WWII and the need to develop military technology. Most of what it’s known about Silicon Valley is typically from the 70s onward, but its story comes from way before that time5. It is a little known fact that Silicon Valley (before it was called that way) has military roots, where brilliant people were creating groundbreaking technology for defense. Some clever folks saw the value in these brilliant minds and their ability to develop complex systems, and they started to inject capital. The capitalists (later called venture capitalists) started to fund the brilliant minds. They didn’t just buy stocks. They invested in growing the organizations from the ground up. The venture capitalists provided lots of cash at a very early stage. In return, they got a large stake and significant influence. It was a small and closed party. The people involved in tech startups could talk around the kitchen table.

So, we can see the difference here between the tech startup and the corporations which gave origin to the concept of the Board. A typical startup does not have a large number of investors. Investors do not have limited access to information. Investors are very close to management. But, more importantly, tech startups deal with complex technical challenges which require special knowledge. Think about one of the most famous tech startup disasters of the last decades, Theranos6, and how each board member was highly accomplished and connected7, yet none of them had any substantial scientific or health care industry experience to understand that they were being deceived by an eccentric, close to psychopathic8 yet charismatic executive who was leading the whole company to a stage 5 cliff by over-promising a product that was as appealing as technically unfeasible. Nobody talks much about the Board’s role in the Theranos disaster, but books9 and documentaries10 about its CEO have been released.

In short, the problem that the Board concept initially came to solve, does not apply for tech startups. The Board, understood in the classic way, is the wrong tool. The Law of the Instrument11, also known as Maslow's hammer, is a cognitive bias that involves an over-reliance on a familiar tool. It basically says: when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. When the only governance system you know is the Board, every organization looks like the Dutch East India Company. You gotta love the irony here: startups brag so much about their innovative approaches, yet they go and choose such archaic methods for their own internal direction and control. The shoemaker’s children usually go barefoot.

Used in the old way, the Board is pointless: a group of loosely coupled individuals spread around the world who act more like diplomats, undersampling the many companies they look after by visiting every now and then. Usually rich guys with a distant hit (an exit, etc) they repeatedly brag about. Predominantly male and technically shallow, they walk around the office space, coffee in hand, asking irrelevant questions, wasting the time of those who are doing actual work, diving (at the most) PowerPoint-deep in what’s going on. You know, living the life, having nice dinners, bringing their relatives along, only to eventually fly away to never be seen again until half a year later when the cycle repeats.

###

Just as Collins’ finishes his book with “well-founded hope” on how companies can recover from almost rotting to death, I will try to finish this article with “well-founded hope” about the Board concept.

The Board system can work, but it must be refurbished. We must forget about the office wandering snobs, and think about assembling a technocratic board with architects. A clique with expertise in areas that startups desperately need: product discovery, complex systems, competitive intelligence, finance, software architecture, strategy, conflict, and a solid grasp on the technology the company is dealing with. A tight and vitally diverse oracle of near-scientist system thinkers, extra-hard to bullshit, and addicted to creating lean, lightweight, healthy organizations. People who cultivate low profiles and simple lifestyles, who despise buzzwords, fads and vapid metrics. Polymaths who can master more than one skill (to keep it small), who have a constant thirst to guide companies go from nothing to good, from good to great, and built to last. Hard to find? Yes, as gold is, which means that a large amount of rock and mud will have to be processed in order to be found.

As an illustrative example, the word governance does not appear a single time in the entire book, whereas the word “CEO” appears 113 times for a roughly 200 pages book.

For comparison, the word board (case independent) appears 34 times.

Elizabeth Holmes (Theranos’ CEO) would reportedly change her tone of voice to a lower baritone tone to sound more credible: https://www.thecut.com/2019/03/why-did-elizabeth-holmes-use-a-fake-deep-voice.html